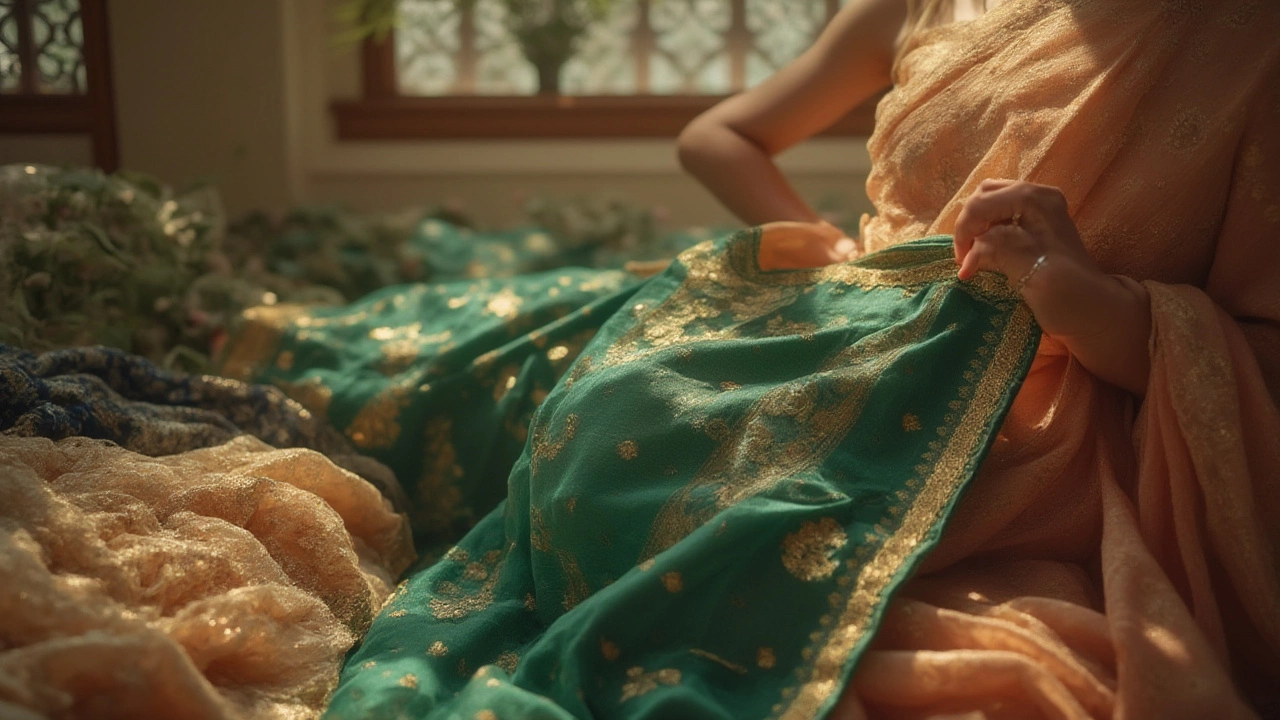

Picture this—someone shows up at a family wedding in a saree so dazzling, you can spot it from the other end of the hall. No, it’s not just the embroidery or shiny sequins stealing the show. The real star? The fabric. In India, wearing expensive fabric isn’t just about showing off money—it’s about tradition, region, art, even pride in our craft. You might think gold and diamonds top the list of luxuries, but sometimes, the fabric alone is worth more than all the bling in the room. What’s driving these sky-high prices? Is it all silk, or does some obscure wool outprice the shiniest Banarasi? Let’s pull back the curtain.

The Royal League: Silk, Pashmina, and Handloom Legends

Few things speak of luxury like silk. Not just any silk, but the legendary Banarasi silk, the regal Kanjeevaram, and the nearly ethereal Mysore silk. Banarasi sarees, for instance, can fetch up to ₹2 lakh or even ₹5 lakh if the zari is woven with real silver or gold thread—yep, actual precious metals in your clothes. A single Banarasi can take between 15 days to six months for an artisan to weave. That’s not just skill, that’s patience on another level. Interestingly, some of Lucknow’s finest chikankari uses rich georgettes and silks but relies more on artistry than fabric cost; Banarasi and Kanjeevaram, though, are always about both.

Pashmina is one fabric that often shocks people with its price tag. The reason? Genuine Pashmina comes from the fine undercoat of Changthangi goats living at high altitude in Ladakh. One scarf can start at ₹10,000 and soar to ₹1 lakh or beyond. A full handwoven shawl, with intricate sozni embroidery, isn’t just a piece of clothing—it’s often an heirloom. And here’s the catch: much of the so-called ‘Pashmina’ in markets is blended. Pure Pashmina is crazy rare and tough to certify unless you know a trusted Kashmiri artisan.

Let’s not skip over the love affair Indians have with handloom weaves. The rarer, the pricier. Take Patola sarees from Gujarat—double ikat, double drama, double price. Each saree can cost upwards of ₹1.5 lakh and might take six months to a year to weave. Real Patola never fades, and a trained eye can spot its intricate, near-symmetrical motifs. Then there’s Kanjeevaram from Tamil Nadu—think lustrous, thick silk with contrasting borders, broad zari, and temple motifs. Prices for pure gold zari weaves easily cross ₹3 lakh. Many film stars and politicians have a Kanjeevaram as a staple, not just for its look but its unmatched drape and weight.

Expensive fabrics India doesn’t just mean high price per metre; it’s about the skills, the designs, and the stories woven in. All these weaves—Paithani from Maharashtra, Baluchari from Bengal, even some versions of Jamdani—are legendary and fiercely expensive, especially when crafted in their purest styles.

The kingly Mulberry silk from Assam’s wild Muga, with its natural golden sheen, is also among the costliest. Unlike most silk, Muga doesn’t need dye because its glow is natural. A Muga saree can easily cost upwards of ₹50,000, and the sheen gets better with each wash. Only Assam’s silkworms can create Muga; it’s not grown anywhere else in the world.

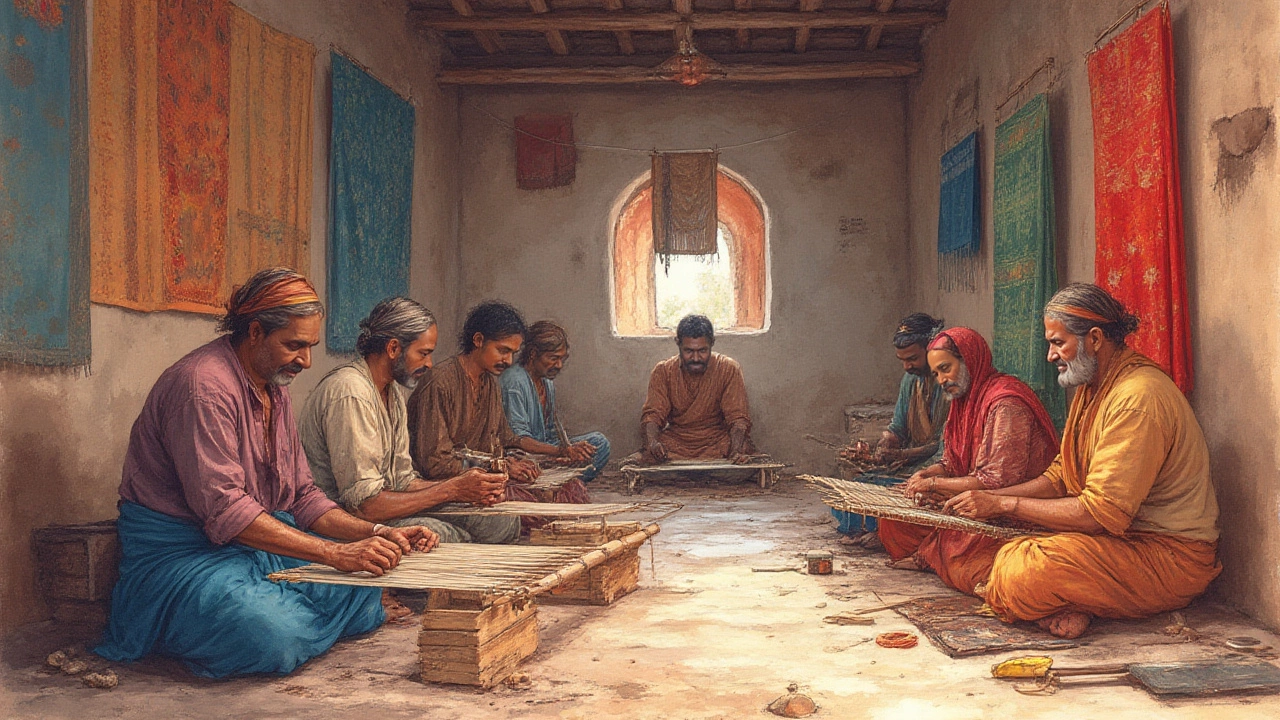

If you’re ever in doubt, just ask the seller about the work hours. Anything taking weeks or months is rarely cheap. The rarest fabrics aren’t always on the rack at your local mall. You’re more likely to stumble upon them at exhibitions, royal wardrobes, or your grandma’s trunk.

What Makes These Fabrics So Expensive?

The price isn’t just about materials. A lot has to do with where and how the fabric is made. For instance, weaving a handloom Patola saree needs two weavers working simultaneously so the patterns align perfectly on both sides—mess up one thread, start over. Kanjeevaram weaving often involves three people at a loom and genuine, hand-beaten gold and silver wire. These aren’t just clothes; they’re art, and every piece is one of a kind.

Pashmina’s cost factors in the remoteness of Ladakh, the harsh winters, and the fact that a goat gives just around 80–150 grams of pashm (wool) per year. Spinning Pashmina is done by hand—try spinning something finer than human hair and see how that feels. The quality check itself is hardcore; only the best fibers pass. This makes the yarn as exclusive as it gets.

Naturally, supply and demand play their part. Authentic handwoven fabrics have limited production because master craftsmen are fewer each year—youngsters prefer office jobs or tech, so the skill is literally dying. Scarcity pushes prices higher. On top of that, imported raw silk, artisan wages, fluctuating gold and silver prices (for zari), logistics, and even government taxes make the final cost balloon. Sometimes, transport out of remote villages is so tricky, one wrong monsoon and the supply is cut off for weeks.

If you want a fun contrast, compare these to machine-made polyesters or viscose, which can cost as little as ₹80-₹300 per metre. You won’t get the same richness, and the environmental toll of the cheap stuff is way higher. Cotton isn’t cheap either, when it’s truly rare—certain indigenous handspun khadi can be pricey, but it’s generally cotton and linen that’s within most budgets, unless you’re looking at rare weaves like Muslin from Bengal. A Dhakai Jamdani, for example, especially old ones, can fetch astronomical prices at auctions because the art is nearly lost.

Here’s a snapshot of fabric prices as of this year:

| Fabric Name | Region | Typical Price Range (per meter/saree) | Main Factors for Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Banarasi Silk | Varanasi (UP) | ₹5,000-₹5,00,000 per saree | Gold/Silver zari, weaving time, heritage |

| Kanjeevaram Silk | Tamil Nadu | ₹10,000-₹3,00,000 per saree | Zari purity, silk weight, motifs |

| Pashmina | Kashmir/Ladakh | ₹10,000-₹2,00,000 per shawl | Pashmina purity, embroidery, rarity |

| Muga Silk | Assam | ₹15,000-₹60,000 per saree | Natural golden hue, locality |

| Patola | Gujarat | ₹1,50,000-₹5,00,000 per saree | Double ikat, labor intensive, rare |

Sometimes, it’s nostalgia driving the price, but practical reasons rule. Real gold-and-silver threads, rare wools, labor-intensive designs, plus artist reputation, all hike things up. One fun fact: some Banarasi saris are so valuable, they get passed as family treasure, just like jewelry. If you see antique pieces, don’t be surprised if they cost even more because the technique might be extinct now.

Another angle? Numbers. About 95% of the silk used for sarees in India is mulberry silk, but only a fraction comes from heritage regions like Kanchipuram. The Paper on Indian Handlooms by the Ministry of Textiles shows a steady 15–20% price rise for certain rare saree types over the last 5 years, despite fewer people buying them each year. Nostalgia and weddings keep demand steady, especially in South India, Mumbai, and Kolkata, for both sentimental and photogenic reasons.

All this means—if you want something affordable and washable, stick to blended or synthetic. But if you want something prized—whether it’s to turn heads at a wedding or to give your future grandchildren—the classics stay unbeatable.

Spotting Genuine Luxury: Tips for Buyers

No one wants to get ripped off, right? Yet with so many lookalikes in markets, it’s easy to fall for a ‘Banarasi’ that’s just art silk or a ‘Pashmina’ that’s mostly viscose. First rule: Check the feel. Pure silk is soft but crisp, and has this unmistakable sheen. Rub it between your fingers; if it heats up fast, it’s more likely to be real. Fakes often feel cold and too smooth because of synthetics. Pure Pashmina, on the other hand, is featherlight and warm—no acrylic can match its softness.

Second, ask tough questions about the source. For Banarasi or Kanjeevaram, demand a silk mark or an authenticity certificate if you’re buying from a reputed shop. Good sellers in Varanasi or Kanchipuram often have photos of their weavers or details of the craft process. You won’t get that in every market, but in places like Mumbai’s designer studios, it’s a big confidence boost.

Inspect the back of the fabric, especially sarees. In a real handloom, you’ll see minor imperfections—tiny threads, slight pattern skips. Machine-made pieces are too symmetric and perfect, almost lifeless. In Patola, for example, both sides are mirror images, but if you look with a magnifier, you’ll see hand-joined knots and tiny color variances—that’s the magic. For Pashmina, try the ring test: a real Pashmina stole will slide easily through a finger ring, proving its fineness. Not foolproof, but a fun party trick!

If you’re buying online, do your homework. Reputed brands rarely sell the real thing super cheap. If that 'Banarasi' saree is under ₹2,000, it’s likely a blend. Most heritage weavers sell through co-op societies or exhibition stalls for a reason—they can’t afford to let middlemen drive prices down.

Keep these tips in mind when picking out true luxury:

- Look for certification: "Silk Mark" for silk, GI tags for region-specific weaves.

- Check artisan or brand reputation. Well-known labels or families are less likely to dupe buyers.

- Ask about the exact origin. Real Pashmina only comes from Ladakh/Kashmir, not from anywhere else.

- If the price seems too good to be true, it usually is.

Always store expensive fabrics with care. Keep them wrapped in muslin or cotton cloth, never in plastic bags. For silks and handlooms, dry cleaning is safer than hand washing, especially for Zari. And seriously, avoid using naphthalene balls—they can discolor real silk or Pashmina.

Sometimes, you’ll find vintage sarees or shawls in family trunks—never cut them up into cushion covers. Restoring and wearing them can be a bigger flex than buying new. Plus, old weaves from the 1960s or earlier often have a quality you just won’t find today.

Thinking of gifting? High-grade fabric—properly chosen—can be a bigger statement than jewelry, especially if you know someone’s personal taste or family tradition. Banarasi for North Indians, Kanjeevaram for Tamilians, Pashmina for wedding winters—you’ve got options.

If you step into Mumbai’s luxury saree boutiques, don’t be shocked to see price tags that outmatch gold chains. The glory of Indian fabric is its variety—each region, artisanal tweak, or rare animal fiber lends something special. In the end, India’s priciest fabrics aren’t just garments: they’re walking, wearable art, and sometimes, they’re the heirs to generations of tradition.